How to Actually Tax the Rich

Every "Tax the Rich" scheme since 1913 has ended up taxing workers instead. It doesn't have to.

There's all kinds of things we don't want people to do. We fine speeders, mandate waiting periods for guns, and add grotesque warning labels on cigarette packs. But anyone with a yellow nicotine stain between their index and middle finger knows exactly which finger those deserve.

The truth is, when we're really serious, we just tax it. Gasoline, tobacco, alcohol. Aluminum cans, plastic bags, and glass bottles. We don't tax them for any real budgetary purpose, they're just disincentives. We discourage things we want less of, through tax policy. And it works. Cans get recycled, smoking rates plummet, and there was that one year where everyone bought cloth grocery sacks.

The verdict is in: taxation disincentivizes whatever gets taxed. Which begs the obvious question, so why do we tax... labor?

Our tax policy is a curious thing, built from patchwork to paper over funding gaps, and riddled with carveouts, carefully constructed loopholes, and the kinds of exemptions that make one wonder, "why do whaling captains in Alaska get special subsistence deductions?" The idea that there's a grand theory to this scheme can be dismissed out of hand.

The origins of income tax are more recent than you'd think. For most of human history, taxes were simple: land taxes, trade duties, or flat fees per person. Plus, the practical reality of bribes, mandatory tithing, and protection money. The idea of taxing a percentage of someone's annual earnings only emerged in the industrial age, when most people stopped owning productive assets and started earning wages instead. America did quite well for 150 years without any income tax at all, until 1913, when Progressives pushed through the 16th Amendment to tax the robber barons. The original pitch: income tax only applied to the wealthiest 1% of Americans. Sound familiar?

In 2024, Federal revenues were $5.1T. Of those, more than three-quarters ($4T) was a direct tax on labor. Payroll taxes, social security, self-employment, independent contractor, and employer-side matching isn't just an important component of our tax base. It is our tax base.

In the end, we got a tax code that has positioned almost the entire societal tax burden against the productive labor of essential workers. This isn't just unfair, it's idiotic. When we transitioned from owning productive assets, like farms, to generating our economy through labor, we made productive capacity the backbone of the economy. And then we started systematically disincentivizing it.

And we didn't have to.

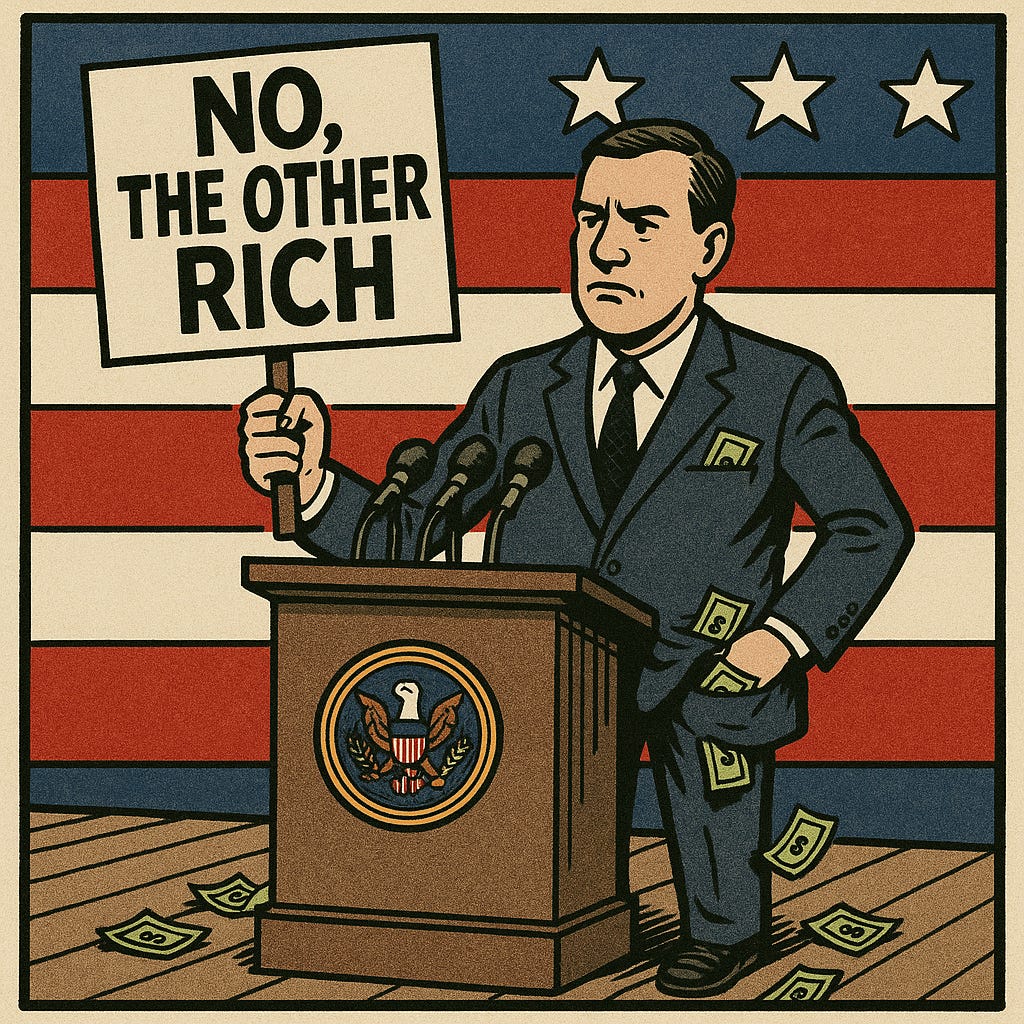

1913's "soak the rich" rhetoric targeted "robber barons" and "millionaires." Today we get "tax the rich" dresses at elite parties, while politicians fly in private jets so they can say, "make billionaires pay their fair share" in front of audiences who'd rather chant mantras than run the math. That isn't justice, it's justification.

The collective wealth of the top 1% of Americans is $48 trillion according to the Federal Reserve’s Distributional Financial Accounts reporting. That sounds impressive, until you do the calculations. Forget for a moment what would happen if you tried to liquidate even a tiny percentage of that wealth.1 Even if you seized 100% of it, found non-wealthy buyers to pay full price for it—which they can't afford—without them having to liquidate their own assets to do it, you're still left with a disappointing answer. When you start $37T in debt, $48T doesn't get you a whole lot. The remaining cash would fund the government for less than two years. Then it's time to have a tough conversation with the two-percent.

That's the practical issue, but unfortunately, it's the least important one. The real problem is that, eventually, you're the problem. Which is why you're paying the robber baron tax, right now.

The ethics of taxation are dubious, at best. They're underpinned by a genuine dilemma: how to pay for the real costs of centralized solutions to common problems. There are ethical answers to that, but none of us think stealing from our neighbor is one of them. Outsourcing to men in polyester suits is just extra steps.

What we want is a system that distributes the load, isn't regressive, doesn't penalize socially positive behavior, can't be easily skirted, folds into our existing institutions, and isn't blatantly coercive.

There is actually a model for this. It's a transaction tax. It often gets dismissed prematurely, because people anchor to the familiarity of "sales tax," but it's quite distinct and resolves the regressive nature of familiar approaches.

Here's how it works: under a transaction tax, everyone pays a small tax on every financial transaction. Say, 2% each from all parties. When you buy something, you pay 2% and the seller pays 2%. But here's where it diverges dramatically from the "sales tax" approach. It applies to all financial transactions: If you earn $1,000, you and your employer each pay $20. That's it. You spend it on rent — another $20 from you, $20 from your landlord. That’s 4% total for the earn/spend cycle. If you earn (or borrow) money once, and spend (or invest) it once—on anything—you'll pay a total of 4% round trip. No income tax. No social security tax. No capital gains tax. Just 2% on every transaction.

Surely this wouldn't be enough! Actually, it would be far more than enough.

Most of the time, when we talk about the size of the economy, what we really mean is: Gross Domestic Product. In the US, we track GDP using the expenditure approach—how much money got spent each year, on new things. Whether it's consumer spending on Netflix or rent, or corporate spending on manufacturing capacity or payroll. But this is a gross2 oversimplification.

The problem isn't in what GDP tracks, but in what it doesn't track: almost anything. No used cars, used houses, or used electronics. Nothing on craigslist, facebook marketplace, eBay, or OfferUp. No financial instruments of any kind; not stocks, bonds, mutual funds, options, gold coins or foreign exchange. And nothing from the shadow economy, cash tips, informal labor, gifts, remittances, collectibles, or bitcoins.

This metric, the actual total transaction volume, is called: nothing. We don't even have a name for it. It's not tracked, or even estimated, by any authoritative or credible agency. And it should be. Because while GDP is an impressive $30 trillion, this figure, the total transaction volume in the US, is almost certainly upwards of $250 trillion, and likely $300 trillion or more.3

Times .04

Let's assume we could only capture transaction tax on $200T of those transactions, just to be safe. If each party pays 2%, that's 4% of $200T, or $8T annually. Compare that to the $5T from our current strategy. It's 60% more tax revenue, without any income taxes at all, by taxing the actual economy, instead. It fully funds current spending, could supplement social security shortfalls, and freeze (if not outright reverse) the debt. And that's even if all that extra money in your pocket doesn't increase total spending. Which, of course, it does.

It would be easy to implement since banks and brokerages intersect the majority of these transactions, and already have to file tax reports on behalf of customers anyway. And it would do a much better job of taxing elite wealth: in trusts, in financial markets, in opaque private transactions. It manages the dual mandate of treating every citizen equally, without being regressive. It wouldn't require liquidation of anyone's assets, doesn't disincentivize workers, and it would be hard to bullshit.

So why don't we?

Because it’s hard to bullshit. Unfortunately, the complexity isn’t a bug, it’s the point. Simple tax systems don't need armies of tax lawyers, accountants, compliance officers, or lobbyists. Remember those Alaskan whaling captains?

But really, it's because complex tax codes aren't even about revenue—they're about control. Politicians can't make threats in a simple system, and they can't offer rewards. With enough complexity, they have a lot of tools: eliminate the deduction for your industry, or add a carve out for your geographic region. They don't want wise taxes, they want leverage. You can see this for yourself, next time you look over all of the boxes you aren't checking in your tax-prep software. Software you only need because financial leeches don't feed on simplicity.

And 2% per transaction is dead simple.

Now, some people will focus on technical implementation details: How do we handle market makers? What about clearinghouse transactions? Others will point to compliance or privacy aspects, like how we track or report. Or whether it exposes sensitive activity. Fair questions with straightforward solutions—we exempt purely internal transfers and define clear categories for infrastructural transactions, like market making. Financial institutions report aggregated totals, protecting individual privacy while automating compliance. Most consumers would never file a tax return again—banks handle everything automatically. April is just another month.

But notice what's missing from that conversation: the usual political theater about who deserves to pay what. That's not an accident. When you tax transactions instead of people, the “fairness” debate becomes irrelevant. Rich people make more transactions, and larger ones, so they pay more. Naturally.

But, next time you hear a politician asking who should pay, remember who actually ends up paying. 2% per transaction pays off our debt in a generation. The “soak the rich” strategy got us $37 trillion in debt instead.

In 2008, about $740 billion in potential fire-sales—equivalent to less than 5% of the one-percent’s wealth at the time—nearly collapsed the global economy. It didn’t even have to actually happen, just the risk was enough.

Pun intended.

GDP ~30 T + existing home sales ~1.7 T + used autos ~1.2 T + other secondary goods ~1 T + public equities turnover (bonafide) ~25 T + fixed-income turnover (kept) ~120 T + derivatives settlements ~30 T + private capital markets ~3 T + insurance premiums & claims ~5 T + royalties/licensing ~0.5 T + foundation/trust transfers ~2 T + loan originations & repayments ~30 T + B2B intermediate inputs ~$45T + other omitted flows (private debt trades, asset swaps) ~15 T ≈ $309.4 T

This intentionally under-estimates financial markets to avoid counting purely mechanical financial plumbing, like market-making, clearinghouses, notional value, etc.