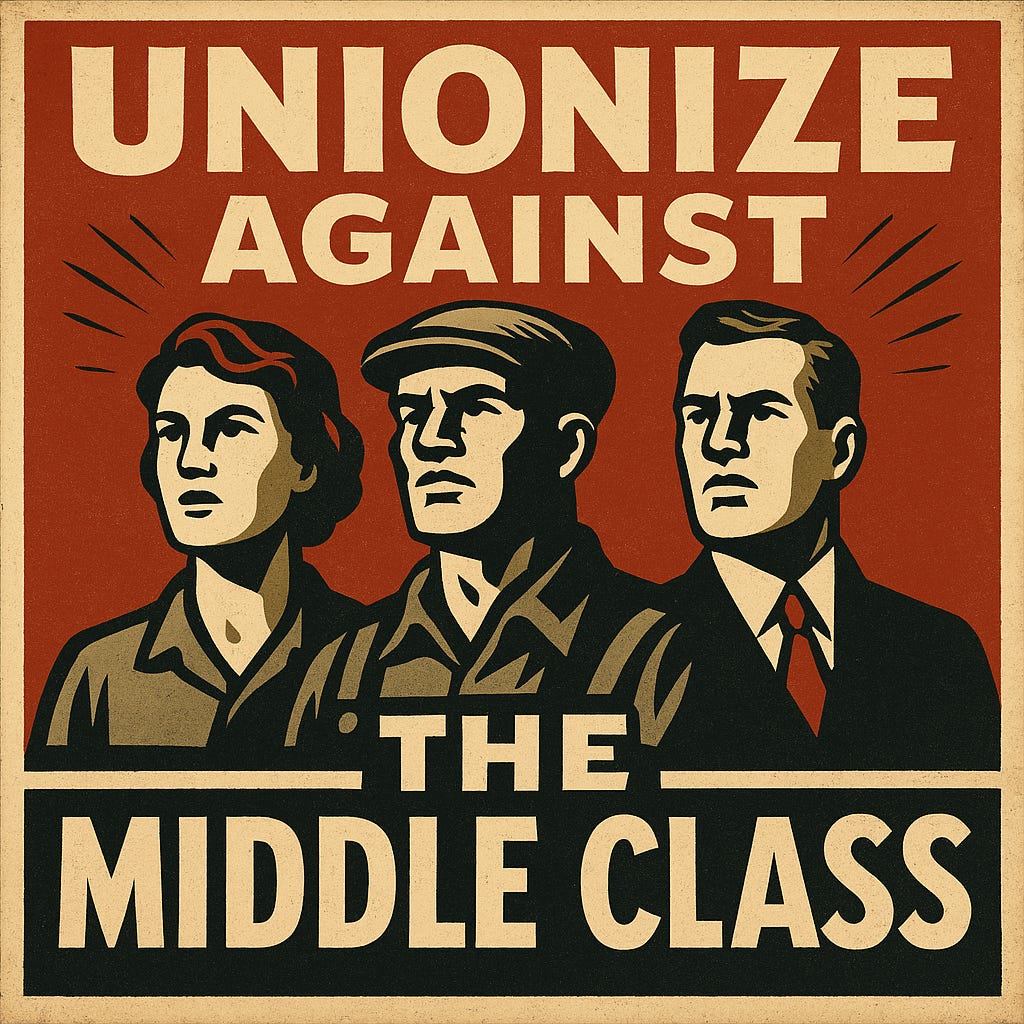

Unionized Against the Middle Class

Public sector unions don't protect the powerless from exploitation from the powerful few. They do the opposite.

Working for a large employer in the 1880s was brutal. Twelve, or even sixteen-hour days and six or seven-day workweeks were not uncommon in heavy industry, with wages so low they barely covered basic living costs, not that you got to do much living. In remote mining towns and company-dominated communities, many employers paid in “scrip,” redeemable only at the company store—an arrangement that let owners claw back much of what they had just paid out. Safety standards were virtually nonexistent: factories, mines, and railroads routinely maimed or killed workers. Saving enough to escape was nearly impossible, leaving most trapped in a cycle of exhaustion, debt, and dependency.

So workers unionized, pooling their labor to demand shorter hours, better pay, and the earliest forms of safety standards. But that picture of steady progress is misleading. Early unions faced ferocious resistance. Courts often branded strikes as “conspiracies in restraint of trade.” Police and federal troops were deployed against strikers, sometimes with deadly results. Companies hired private militias and strikebreakers to beat back organizing efforts. In short, the system was stacked against labor.

In time, union strength grew. Union halls became not just bargaining centers but also spaces of solidarity, political education, and community aid. By 1935, the Wagner Act legalized collective bargaining and prohibited many anti-union tactics. The government had switched sides. After this, unions secured pensions, health insurance, and work rules that defined mid-20th-century “middle-class” jobs.

Fast forward to today, and the picture looks very different. The most powerful unions now are in the public sector, representing government employees who bargain not against industrial barons in the interest of safety, but against working taxpayers and their accountability—the descendants of the very people unions were created to protect. These public sector "unions" aren't unions at all in any historical sense.

The Linguistic Trap

The semantic confusion isn't accidental—it's politically essential. By calling both arrangements "unions," we import the moral legitimacy of the original labor movement into an entirely different institutional relationship. But when we strip away the rhetoric, the distinction becomes stark: private sector unions organize workers against employers who can go bankrupt; public sector unions organize government employees against taxpayers who cannot.

The mechanism of unions comes from "collective bargaining." These negotiations rely on a basic premise that both sides have rational interests and that the negotiation is based on practical constraints. Push too hard in either direction, and the company fails, jobs disappear, and everyone loses. This creates natural boundaries around union demands and employer resistance, encouraging productive compromise toward a symbiotic relationship.

Public sector unions face no such limits. They can demand ever-increasing compensation and benefits paid by a revenue source—taxation—that cannot go out of business, cannot relocate, and cannot choose alternative providers. Plus they control the monopoly on force to collect it. In these negotiations, the government sits at both sides of the table—as employer and union—and negotiates not with its own profits, but with yours. This is not labor protection.

When "Public Servants" Organize Against the Public

When teachers, bureaucrats, municipal workers, and other "public servants" unionize, they're always organizing against their actual employer: the public. These aren't powerless workers facing exploitative barons—they're government employees with civil service protections, defined-benefit pensions, and job security that private sector workers can only dream of. According to the government's own data, public sector workers receive benefits equal to 59% of their earnings, compared to just 35% for private sector workers. Rather than demanding their fair share of the value of their labor, they're demanding a larger share of the value of everyone's labor. They have stronger legal protections, more generous healthcare, earlier retirement options, and virtual immunity from performance-based dismissal.

The contradiction becomes more perverse when you consider the mechanisms of accountability. When voters elect politicians who campaign on reducing government spending, public sector unions mobilize to thwart that democratic mandate. They're not fighting corporate exploitation—they're fighting against democracy.

The Chicago Laboratory: Financial Destruction in Real Time

Chicago provides the perfect case study in how public sector unions capture democratic institutions and systematically destroy public finances. The Chicago Teachers Union didn't just elect one of their own organizers as mayor—they bought him outright, spending $2.3 million to install Brandon Johnson in office.

The financial carnage has been swift and brutal. Johnson immediately demanded that Chicago Public Schools take out a $300 million high-interest loan to fund generous CTU contract increases, despite CPS already drowning in $9.3 billion of debt and paying $817 million annually just in interest. When his own hand-picked school board refused—recognizing that borrowing money to pay union contracts would accelerate the district's financial collapse—Johnson forced all seven members to resign and replaced them with more compliant appointees.

Even that wasn't enough. When the new board still balked at what CPS staff called "fictional or phantom revenue," Johnson pushed out the schools' CEO for putting fiscal responsibility ahead of union loyalty. By September 2025, facing a $734 million deficit, Johnson repeated the same pattern: demanding high-interest borrowing to avoid confronting CTU contract costs, bypassing resistant administrators, and pressuring board members directly.

The beneficiary of this financial chaos? The Chicago Teachers Union, whose members secured raises while the district's capacity to pay evaporated. The results speak for themselves: Chicago ended 2024 with a $146 million shortfall, faces a $1.2 billion budget gap in 2026, and has seen its credit rating downgraded toward junk status. A city with 2.7 million constituents is toying with financial collapse to fund raises for 30,000 public union members. This isn't education policy—it's municipal extortion, with taxpayers held hostage to union demands funded by borrowed money the city cannot afford to repay.

The Deficit-Spending Shell Game

Most people have an intuition that taking away previously defined pension benefits is unjust. But, insidiously, governments weaponize this fair-mindedness through a temporal arbitrage—buying political coalitions today with promises against tomorrow's tax revenue. Chicago's pension obligations—now consuming over $800 million annually—represent decades of such deals. Politicians long gone from office negotiated generous retirement benefits that current and future taxpayers must fund, whether they voted for those officials or not.

Government "employers" seemingly believe they can defer costs indefinitely through deficit spending—an option unavailable to private sector employers and anyone with a calculator. When unions extract unsustainable concessions, private companies face immediate consequences: bankruptcy, layoffs, or closure. Government entities simply externalize costs onto future generations through borrowing and unfunded pension liabilities.

The result is a systematic transfer of wealth from future generations to current government employees, with no mechanism for democratic accountability. Those who will pay the bills—children and future residents—have no vote in the negotiations that determine their tax burden.

Resisting Democratic Accountability

When elected officials actually try to implement the spending reductions their voters demanded, public sector unions deploy unprecedented resistance. Trump's Schedule F initiative proposes reclassifying up to 50,000 federal employees—about 2% of the civil service—as at-will, removing many longstanding protections. The plan has sparked massive opposition—drawing over one million public comments and legal challenges from unions—even though no employees have yet been reclassified.

The reaction revealed the stakes. Federal unions immediately mobilized to block any reforms whatsoever, claiming that civil service protections are essential to democracy. But as we've seen, this doesn't protect democracy, it thwarts it. These aren't protections for the vulnerable—they're job guarantees for a permanent governing class that increasingly views itself as independent from democratic accountability, voters be damned.

The "deep state" isn't simply a MAGA talking point—it's an employment category. When public union members can't be dismissed for performance, policy disagreement, or through democratic election—unaccountable to both public will and executive authority—they become conspirators, not conspiracy theories.

Resolving the Labor Metaphor

Fortunately, the solution isn't complicated: ban public sector collective bargaining entirely. Government employees should have the same workplace protections as private sector workers—safety regulations, non-discrimination laws, reasonable hours, and grievance procedures. But they shouldn't have the power to hold taxpayers hostage through strikes, slowdowns, political manipulation, or outright refusal of democratic direction-setting.

Public employment is a public service, not an individual right. These positions exist to enact public will, not provide lifetime sinecures for politically connected workers. When government employees organize against the people who employ them—and who already provide them better compensation and job security than private sector workers receive—they've abandoned the premise of labor rights entirely.

Unless we ban these government unions, we'll inevitably duplicate the Chicago model nationwide: governance by and for government workers, with taxpayers relegated to coerced funding streams to the benefit of unionized political control. The result: public finances destroyed by unsustainable commitments, democratic processes captured by special interests, and public services subordinated to administrative enrichment.

Labor unions served their purpose when they protected powerless workers from powerful employers. 150 years later, these public unions look less like the early labor organizers fighting for basic dignity, and much more like the robber-barons they once opposed—a self-aggrandizing few who enrich themselves by externalizing costs onto the powerless many. It's time to end the charade and restore the principle that public servants actually serve the public, not themselves.