Too Much Health Insurance: The Paradox of American Healthcare

America's bizarre healthcare system doesn't suffer from too little insurance—it's drowning in it. What if our obsession with "coverage" is actually making medicine unaffordable?

In a nation perpetually obsessed with expanding healthcare coverage, we’ve somehow missed the most glaring irony of all: America doesn’t suffer from a shortage of health insurance—we’re drowning in it. The endless hand-wringing over universal coverage has obscured a more fundamental problem that nobody wants to acknowledge: health insurance itself has become the disease.

When Insurance Stopped Being Insurance

Insurance, by definition, exists as a financial instrument to protect against catastrophic, unpredictable losses. It’s a hedge against black swan events—the house fire, the major car collision, the hurricane damage to your property, or the theft of valuable possessions. We don’t expect our homeowner’s policy to cover lightbulb replacements or lawn care, yet somehow we’ve convinced ourselves that health insurance should cover everything from routine checkups to common prescriptions.

This arrangement would be laughable in any other context. Imagine paying $500 monthly for car insurance that covers oil changes, windshield wiper replacements, and gasoline—with a $50 copay, of course. Picture your mechanic spending half their time submitting paperwork to your car insurer to prove that your transmission fluid actually needed changing. The friction would be staggering, the costs astronomical, and the service abysmal. Yet this is precisely the system we’ve not only accepted but vigorously defend in healthcare.

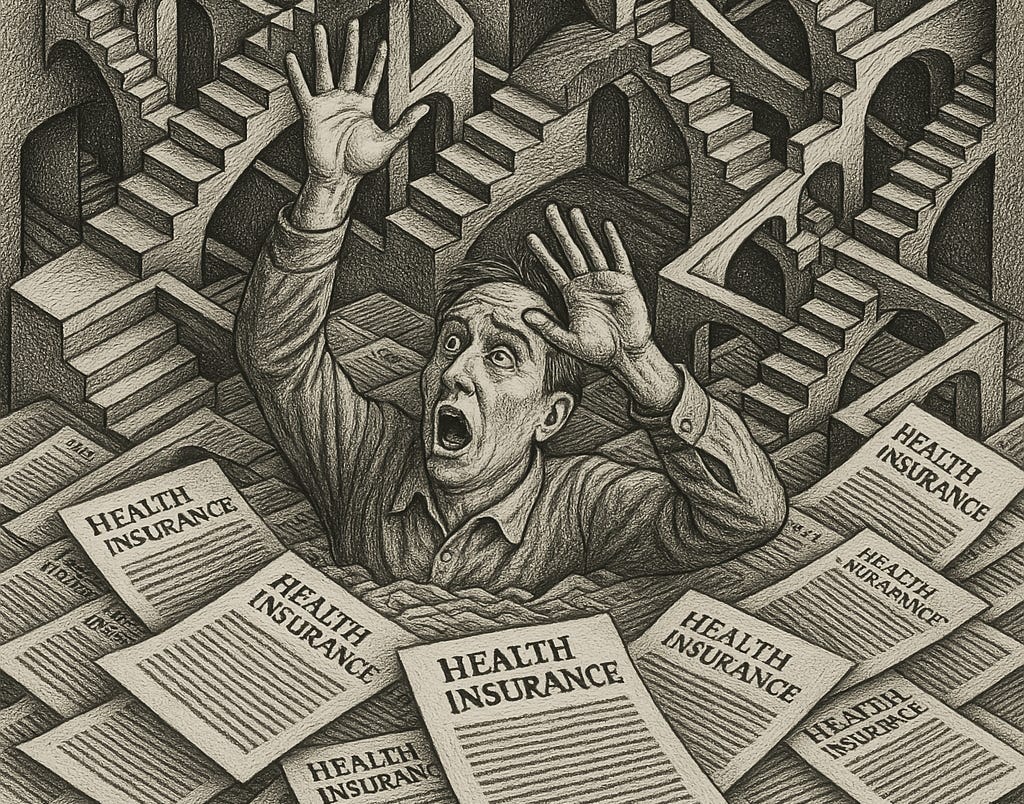

Every day across America, medical teams navigate labyrinthine insurance requirements, clinicians compromise their treatment plans to fit insurance algorithms designed in boardrooms rather than exam rooms, needed medications are denied until multiple appeals are filed, and patients schedule appointments months in advance only to spend more time in waiting rooms than with providers. The bureaucratic quagmire isn’t theoretical—it’s the daily reality of American healthcare, and we’re paying through the nose for every frustrating minute of it.

The contradictions in our approach become even more apparent when we consider what health insurance explicitly excludes: your eyes and teeth. Apparently, these anatomical features—despite being connected to your nervous system and bloodstream—aren’t “health”-enough to warrant coverage under standard plans. This separation actually reveals an important truth: dental and vision care, with their predictable cleanings and annual prescription updates, don’t belong in insurance at all. This isn’t a bug in the system; it’s a tacit admission that the insurance model should only cover unpredictable, catastrophic events—not routine care.

The Bureaucratic Middleman

The insertion of insurance companies between patients and routine healthcare has created a bureaucratic leviathan that devours resources while adding minimal value. Instead of vetting the legitimacy of a small number of catastrophic claims, now each transaction, no matter how trivial or mundane, must pass through an administrative gauntlet: coding, billing, reviewing, denying, appealing, resubmitting, negotiating, and finally—if the stars align—paying.

This Byzantine process doesn’t come cheap. Approximately 15-30% of healthcare spending in America goes not toward actual care but toward administrative costs—a staggering misallocation unique to our system. Every dollar siphoned into this bureaucratic black hole is a dollar not spent on improving health outcomes.

More perniciously, this arrangement has fundamentally altered the doctor-patient relationship. When physicians became primarily accountable to insurance companies rather than patients, the core incentives of medicine shifted. Doctors now spend more time documenting to satisfy billing requirements than actually listening to patients. The question “What does this patient need?” has been supplanted by “What will insurance cover?”

This isn’t about physician greed—it’s about survival in a system where medical education leaves doctors hundreds of thousands of dollars in non-dischargeable debt. Physicians have little choice but to prioritize insurance reimbursement mechanisms that will allow them to keep their practices open, make payroll for their staff, and gradually pay down their massive student loans. The bureaucratic demands further squeeze the already limited time they can spend with each patient, degrading care while increasing costs.

The Coverage Mirage

The great irony of American healthcare is that despite our fixation on insurance coverage, we’ve created a system where insurance itself has become the primary driver of unaffordability. Between employer-sponsored plans, Medicare, Medicaid, state supplemental programs, and ACA marketplace options, most Americans have some form of coverage, at least technically. Yet the very mechanism intended to make healthcare affordable has made it anything but.

The system’s dysfunction manifests in particularly costly ways. Despite coverage, millions of Americans still use emergency rooms as their de facto primary care provider—not from ignorance, but because the insurance-distorted system makes it the path of least resistance. It’s the single mother who faces a brutal choice: lose half a day’s wages for a clinic appointment during business hours, or take her feverish child to the ER after her shift ends. It’s the recovering addict seeking not just treatment but shelter, and the immigrant who can’t navigate labyrinthine phone systems but knows one place they can’t legally be turned away. This occurs not from patient ignorance but from rational response to a broken incentive structure designed for fictional Americans with unlimited flexibility, bottomless patience for bureaucracy, and the superhuman ability to schedule illnesses weeks in advance. When faced with the Kafkaesque maze of in-network providers, bankers’ hours, prior authorizations, and inscrutable coverage exclusions, the ER’s federally-mandated open door becomes the only reliable option. The $2,000 bill for what should be a $100 treatment then ripples through the system, bloating premiums in an endless cycle of institutional dysfunction.

This distortion affects everyone—even those who can’t afford or choose not to purchase insurance. The “chargemaster” rates that hospitals and providers maintain are artificially inflated to maximize reimbursement from insurers, creating an absurd parallel universe where the listed price bears no relation to actual costs. The uninsured patient doesn’t face the true market rate; they face these grotesquely inflated prices designed for insurance negotiation games. Meanwhile, those with insurance find themselves trapped in narrow networks, discovering that their insurance card is little more than a plastic talisman with no power at the highest-quality facilities.

The Consumer Disconnection

Perhaps the most damaging aspect of our insurance-centric system is how it has systematically disconnected consumers from the true cost of healthcare. When patients are responsible for only a $20 copay regardless of whether a procedure costs $200 or $2,000, they have no incentive to question necessity or seek more cost-effective options. This disconnection fuels a healthcare inflation spiral that shows no signs of abating.

The counterargument—that medical decisions are too complex for consumers to make rationally—inadvertently makes the strongest case against the current system. If healthcare choices are indeed too complicated for individuals to navigate, why have we created a system that requires patients to become experts in deductibles, coinsurance, out-of-network charges, prior authorizations, and formulary tiers just to access care? And why do pharmaceutical companies spend billions annually advertising prescription medications directly to these supposedly incompetent decision-makers? The contradiction is glaring: patients are simultaneously deemed too uninformed to make cost decisions about generic medications but sufficiently sophisticated to demand specific brand-name drugs from their doctors after watching a 30-second commercial featuring smiling people in fields of flowers.

Ironically, for all this complexity, we’ve failed to incentivize the one, simple area where consumer choice could make a real difference: preventive health. The knowledge that diet, exercise, and lifestyle choices determine approximately 80% of health outcomes remains an inconvenient truth in a system profiting from treatment rather than prevention. This disconnect reflects a fundamental misalignment of time horizons: when patients frequently change insurers every few years, companies have little financial incentive to invest in preventive measures whose benefits might accrue to their competitors decades later, regardless of how profoundly these interventions improve health outcomes.

This disconnect between what truly drives health and what our system prioritizes reveals the need for fundamental reform—one that reestablishes healthcare’s proper priorities and the relationships between patients, providers, and the financial instruments that should serve them, not control them.

Reimagining Healthcare Without the Middleman

A more rational approach would return insurance to its proper role: protection against unpredictable, catastrophic expenses. Routine care—from primary visits to common prescriptions—would operate on a direct payment model, creating a genuine market with transparency, competition, and yes, targeted subsidies for those who need them.

This isn’t a theoretical proposition. Direct primary care practices, where patients pay monthly membership fees directly to physicians (typically $50-$100) in exchange for comprehensive primary services, have demonstrated remarkable success. Without insurance overhead, these practices reduce costs by up to 40% while providing more personalized care and greater physician and patient satisfaction.

For medications, the cash price (without insurance) is often cheaper than copays—a revelation that only becomes apparent when consumers step outside the insurance bubble. Companies like GoodRx have built entire business models around the shocking inefficiency of drug pricing within insurance networks.

Even for more complex care, surgery centers operating on cash-based models have achieved price reductions of 60-90% compared to insured rates, while maintaining quality and dramatically improving customer service. When patients become direct customers rather than insurance revenue codes, the incentives realign toward value and satisfaction.

The Path Forward

The solution isn’t abolishing health insurance but restoring it to its proper function: a financial safety net for major, unpredictable health events. Routine and predictable care belongs in a direct payment model, where transparency, competition, and consumer choice can create genuine efficiency.

The greatest obstacle isn’t practical but psychological. Few defend our current system, yet every proposed solution involves more insurance, not less—whether private or single-payer. The debate centers endlessly on who should pay, never questioning whether “insurance” for routine care makes sense at all. This fundamental insight—that what we call “health insurance” stopped being actual insurance decades ago—remains strangely absent from public discourse.

The evidence is hiding in plain sight. When patients pay directly for care—whether at cash-pay surgery centers, direct primary care practices, or when purchasing medications outside insurance networks—prices plummet while satisfaction soars. The moment we remove the administrative overhead from the equation, healthcare suddenly becomes remarkably affordable and customer-focused.

In our misguided quest to insure everything, we’ve created a system that satisfies no one—not patients, not providers, not employers, not even insurers themselves. Perhaps it’s time to consider that the problem isn’t that we have too little health insurance, but that we have far too much.